Napoleon Art and Court Life in the Imperial Palace Catalog Pdf

| Joséphine | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

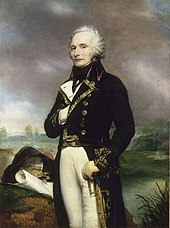

Portrait past Antoine-Jean Gros, c. 1809 | |||||

| Empress espoused of the French | |||||

| Tenure | 18 May 1804 – 10 January 1810 or 14 December 1809 | ||||

| Coronation | 2 December 1804 | ||||

| Queen consort of Italy | |||||

| Tenure | 26 May 1805 – 14 December 1809 or x January 1810 | ||||

| Beginning Lady of Italia | |||||

| Tenure | 26 January 1802 – 17 March 1805 | ||||

| Born | Marie Josèphe Rose Tascher de La Pagerie (1763-06-23)23 June 1763 Les Trois-Îlets, Martinique | ||||

| Died | May 29 1814, historic period (50) Rueil-Malmaison, Kingdom of France | ||||

| Burial | St Pierre-St Paul Church, Rueil-Malmaison, French republic | ||||

| Spouse | Alexandre de Beauharnais (grand. ; died ) Napoleon I, Emperor of the French (thou. ; div. ) | ||||

| Effect |

| ||||

| |||||

| Firm | Beauharnais | ||||

| Father | Joseph Gaspard Tascher de La Pagerie | ||||

| Mother | Rose Claire des Vergers de Sannois | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||

| Signature |  | ||||

Joséphine Bonaparte (French: [ʒozefin bɔnapaʁt], born Marie Josèphe Rose Tascher de La Pagerie; 23 June 1763 – 29 May 1814) was Empress of the French as the get-go wife of Emperor Napoleon I. She is widely known as Joséphine de Beauharnais (French: [ʒozefin də boaʁnɛ]).

Her matrimony to Napoleon was her second. Her first husband, Alexandre de Beauharnais, was guillotined during the Reign of Terror, and she was imprisoned in the Carmes Prison until five days afterwards his execution. Through her children by Beauharnais, she was the grandmother of the French emperor Napoleon III and the Brazilian empress Amélie of Leuchtenberg. Members of the electric current imperial families of Sweden, Denmark, Belgium, and Norway and the grand ducal family of Grand duchy of luxembourg also descend from her. Because she did non comport Napoleon whatever children, he had their spousal relationship annulled in 1810 and married Marie Louise of Austria. Joséphine was the recipient of numerous love letters written by Napoleon, many of which still exist.

A patron of art, Joséphine worked closely with sculptors, painters and interior decorators to constitute a unique Consular and Empire style at the Château de Malmaison. She became one of the leading collectors of different forms of art of her fourth dimension, such as sculpture and painting.[1] The Château de Malmaison was noted for its rose garden, which she supervised closely.

Name [edit]

Although she is often referred to as "Joséphine de Beauharnais", information technology is not a name she e'er used in her lifetime, as "Beauharnais" is the proper noun of her kickoff husband, which she ceased to utilize upon her marriage to Napoleon, taking the last name "Bonaparte"[2] while she did non use the proper name "Joséphine" earlier meeting Napoleon, who was the first to brainstorm calling her such, maybe from a middle name of "Josèphe". In her life before Napoleon, the woman now known equally Joséphine went by the name of Rose, or Marie-Rose, Tascher de la Pagerie, later de Beauharnais, and she sometimes reverted to using her maiden-name of Tascher de la Pagerie in later life. After her marriage to the and so General Bonaparte, she adopted the name Joséphine Bonaparte and the name of "Rose" faded into her past. The misnomer "Joséphine de Beauharnais" commencement emerged during the restoration of the Bourbons, who were hesitant to refer to her by either Napoleon's surname or her Imperial championship and settled instead on the surname of her tardily showtime husband.[ citation needed ]

Early life and showtime marriage [edit]

Marie Josèphe Rose Tascher de La Pagerie was built-in in Les Trois-Îlets, Martinique, to a wealthy French family that endemic a sugarcane plantation, which is now a museum.[3] She was the eldest girl of Joseph-Gaspard Tascher (1735–1790), knight, Seigneur de (lord of) la Pagerie, lieutenant of Troupes de Marine, and his wife, the former Rose-Claire des Vergers de Sannois (1736–1807), whose maternal grandfather, Anthony Brown, may have been Irish gaelic.[4]

The family unit struggled financially after hurricanes destroyed their estate in 1766. Edmée (French, Desirée), Joséphine's paternal aunt, had been the mistress of François, Marquis de Beauharnais, a French aristocrat. When François's health began to fail, Edmée arranged the advantageous union of her niece, Catherine-Désirée, to François'south son Alexandre. This marriage would be highly beneficial for the Tascher family, considering it kept the Beauharnais money in their hands; nonetheless, 12-year-old Catherine died on xvi October 1777, before she could leave Martinique for France. In service to their aunt Edmée's goals, Catherine was replaced by her older sis, Joséphine.[5]

In Oct 1779, Joséphine went to France with her begetter. She married Alexandre on thirteen Dec 1779, in Noisy-le-Chiliad. They had two children: a son, Eugène de Beauharnais (1781–1824), and a daughter, Hortense de Beauharnais (1783–1837) (who afterward married Napoleon's brother Louis Bonaparte in 1802). Joséphine and Alexandre's marriage was non a happy i. Alexandre abandoned his family for over a year in a brief tryst and often frequented whorehouses, leading to a court-ordered separation during which Josephine and the children lived at Alexandre's expense in the Pentemont Abbey, run by a group of Bernardian nuns. On 2 March 1794, during the Reign of Terror, the Committee of Public Safety ordered the arrest of her husband. He was jailed in the Carmes prison in Paris. Considering Joséphine equally too close to the counter-revolutionary financial circles, the Commission ordered her arrest on 18 April 1794. A warrant of arrest was issued against her on ii Floréal, yr II (21 April 1794), and she was imprisoned in the Carmes prison house until 10 Thermidor, year II (28 July 1794). During this fourth dimension, Joséphine was only allowed to communicate with her children by their scrawls on the laundry list, which the jailers soon prohibited.[four]

Her husband was accused of having poorly defended Mainz in July 1793, and beingness considered an aristocratic "suspect", was sentenced to decease and guillotined, with his cousin Augustin, on 23 July 1794, on the Place de la Révolution (today'due south Place de la Concorde) in Paris. Joséphine was freed 5 days later on, thank you to the fall and execution of Robespierre, which ended the Reign of Terror. On 27 July 1794 (9 Thermidor), Tallien arranged the liberation of Thérèse Cabarrus, and soon subsequently that of Joséphine.[four] In June 1795, a new police force immune her to recover the possessions of Alexandre.

Matrimony to Napoleon [edit]

Madame de Beauharnais had affairs with several leading political figures, including Paul François Jean Nicolas Barras. In 1795, she met Napoleon Bonaparte, half dozen years her junior, and became his mistress. In a letter to her in December, he wrote, "I awake total of you. Your epitome and the memory of concluding night's intoxicating pleasures has left no residual to my senses." In January 1796, Napoleon Bonaparte proposed to her and they were married on 9 March. On the marriage certificate, Joséphine reduced her age by 4 years and increased Napoleon'southward by 18 months, making the newly-weds announced to be roughly the same age.[half-dozen] Until meeting Bonaparte, she was known equally Rose, but Bonaparte preferred to call her Joséphine, the name she adopted from then on.[7]

The marriage was not well received by Napoleon'southward family unit, who were shocked that he had married an older widow with two children. His mother and sisters were specially resentful of Joséphine, equally they felt clumsy and unsophisticated in her presence.[viii] Two days subsequently the wedding ceremony, Bonaparte left Paris to pb a French army into Italy. During their separation, he sent her many beloved messages. In February 1797, he wrote: "Y'all to whom nature has given spirit, sweet, and dazzler, you who lonely tin move and dominion my center, yous who know all too well the accented empire you exercise over it!" However, Josephine rarely wrote back and when she did, her letters were dry and often tepid.[ citation needed ] It is known that Josephine did not dearest Napoleon equally much as he loved her, and that it took her years before she warmed to his affections.[ citation needed ] After their marriage, Napoleon was said to have kept a motion picture of her in his pocket which he would found many kisses on every passing hr. Josephine, however, never even looked at the picture of her new married man that Napoleon gave her.[ commendation needed ]

Joséphine, left backside in Paris, in 1796 began an affair with a handsome Hussar lieutenant, Hippolyte Charles.[ix] Rumors of the affair reached Napoleon; he was infuriated, and his love for her changed entirely.[10]

In 1798, Napoleon led a French army to Egypt. During this entrada, Napoleon started an matter of his own with Pauline Fourès, the wife of a inferior officer, who became known as "Napoleon's Cleopatra." The relationship betwixt Joséphine and Napoleon was never the same later on this.[11] His letters became less loving. No subsequent lovers of Joséphine are recorded, simply Napoleon had sexual diplomacy with several other women. In 1804, he said, "Power is my mistress."[12]

In Dec 1800, Joséphine was near killed in the Plot of the rue Saint-Nicaise, an endeavour on Napoleon's life with a bomb planted in a parked cart. On 24 Dec, she and Napoleon went to see a performance of Joseph Haydn's Creation at the Opéra, accompanied by several friends and family. The party travelled in two carriages. Joséphine was in the 2d, with her daughter, Hortense; her pregnant sister-in-law, Caroline Murat; and General Jean Rapp.[thirteen] Joséphine had delayed the party while getting a new silk shawl draped correctly, and Napoleon went ahead in the first wagon.[14] The flop exploded as her wagon was passing. The flop killed several bystanders and one of the carriage horses, and blew out the carriage's windows; Hortense was struck in the paw past flying drinking glass. In that location were no other injuries and the party proceeded to the Opéra.[15]

Empress of the French [edit]

Napoleon was elected Emperor of the French in 1804, making Joséphine empress. The coronation ceremony, officiated past Pope Pius VII, took place at Notre-Dame de Paris, on 2 December 1804. Following a pre-arranged protocol, Napoleon first crowned himself, and then put the crown on Joséphine'south head, proclaiming her empress.

In her office equally empress, Napoleon had a court appointed to her and reinstated the offices which composed the household of the queen earlier the French revolution, with Adélaïde de La Rochefoucauld as Première dame d'honneur, Émilie de Beauharnais as Dame d'atour, and the wives of his own officials and generals, Jeanne Charlotte du Lucay, Madame de Rémusat, Elisabeth Baude de Talhouët, Lauriston, d'Arberg, Marie Antoinette Duchâtel, Sophie de Segur, Séran, Colbert, Savary and Aglaé Louise Auguié Ney, as Dame de Palais.[4]

Shortly earlier their coronation, at that place was an incident at the Château de Saint-Deject that nearly sundered the marriage betwixt the two. Joséphine caught Napoleon in the bedroom of her lady-in-waiting, Élisabeth de Vaudey, and Napoleon threatened to divorce her equally she had not produced an heir. Eventually, nevertheless, through the efforts of her daughter Hortense, the ii were reconciled.[xvi]

When afterwards a few years information technology became clear she could non have a child, Napoleon, while still loving Joséphine, began to think almost the possibility of an disparateness. The final die was cast when Joséphine's grandson Napoléon Charles Bonaparte, who had been declared Napoleon's heir, died of croup in 1807. Napoleon began to create lists of eligible princesses. At dinner on 30 Nov 1809, he let Joséphine know that — in the involvement of France — he must notice a wife who could produce an heir. Joséphine agreed to the divorce then the Emperor could remarry in the hope of having an heir. The divorce ceremony took place on 10 January 1810 and was a grand but solemn social occasion, and each read a argument of devotion to the other.[17]

On 11 March, Napoleon married Marie-Louise of Austria past proxy;[eighteen] the formal ceremony took place at the Louvre in April.[19] Napoleon in one case remarked that despite her quick infatuation with him "It is a womb that I am marrying".[20] Even later on their separation, Napoleon insisted Joséphine retain the title of empress. "It is my will that she retain the rank and title of empress, and specially that she never doubt my sentiments, and that she ever agree me as her best and love friend."

Subsequently life and expiry [edit]

[edit]

Later the divorce, Joséphine lived at the Château de Malmaison, near Paris. She remained on good terms with Napoleon, who one time said that the only thing to come betwixt them was her debts. (Joséphine remarked privately, "The only thing that ever came betwixt usa was my debts; certainly non his manhood."—Andrew Roberts, Napoleon.) In April 1810, by letters patent, Napoleon created her Duchess of Navarre. Some claim Napoleon and Josephine were notwithstanding secretly in love, though it is impossible to verify this.[21]

In March 1811, Marie Louise delivered a long-awaited heir, Napoleon II, to whom Napoleon gave the title "King of Rome". Two years later Napoleon arranged for Joséphine to run across the young prince "who had cost her so many tears".

Château de Malmaison well-nigh Paris

Death [edit]

Joséphine died in Rueil-Malmaison on 29 May 1814, soon later on walking with Emperor Alexander I of Russia in the gardens of Malmaison, where she allegedly begged to join Napoleon in exile. She was buried in the nearby church building of Saint Pierre-Saint Paul[22] in Rueil. Her daughter Hortense is interred near her.

Napoleon learned of her expiry via a French journal while in exile on Elba, and stayed locked in his room for ii days, refusing to see anyone. He claimed to a friend, while in exile on Saint Helena, that "I truly loved my Joséphine, but I did not respect her."[23] Despite her numerous affairs, eventual wedlock annulment, and remarriage, the Emperor's last words on his death bed at St. Helena were: "France, the Army, the Caput of the Army, Joséphine."("France, l'armée, tête d'armée, Joséphine").[24]

Disputed birthplace [edit]

Henry H. Breen, Start Mayor of Castries, published The History of St. Lucia in 1844 and stated on page 159 that:

"I accept met with several well-informed persons in St. Lucia, who entertain the conviction that Mademoiselle Tascher de La Pagerie, better known every bit Empress Josephine, was born in the island of Saint Lucia and not Martinique equally commonly supposed. Amongst others the late Sir John Jeremie appears to have been strongly pressed with the thought.

The grounds of conventionalities residuum upon the following circumstances to which I discover allusions are made in a St. Lucia paper in 1831: 'It is alleged that the de Taschers were amidst the French families that settled in St. Lucia after the Peace of 1763; that upon a small manor on the acclivity of Morne Paix Bouche (which was called La Cauzette), where the future Empress first saw low-cal on the 23rd of June of that year; and they continued to reside at that place until 1771, at which menstruation the father was selected for the important office of the Intendant of Martinique, whither he immediately returned with his family.'

These circumstances are well known to many respectable St. Lucian families, including the late Mme. Darlas Delomel and One thousand. Martin Raphael who were among Josephine's playmates at Morne Paix Bouche. Yard. Raphael being in French republic many years after, was induced to pay a visit to Malmaison on the strength of his sometime acquaintance, and met with a gracious reception from the Empress-Queen Dowager."

Henry Breen too received confirmation from Josephine's former slave nanny called "Dede", who claimed she nursed Josephine at La Cauzette. Josephine'south baptism was administered by Père Emmanuel Capuchin at Trois-Ilets but he has only stated she had been baptised in that location but not built-in. Dom Daviot, parish priest in Gros Islet, wrote a letter to i of his friends in Haute-Saône in 1802 in which he states: "it is in the vicinity of my parish that the married woman of the first consul was born," at the time, Paix Bouche was a part of Castries; he asserts that he was well acquainted with Josephine'southward cousin who was a parishioner.

Josephine's father owned an manor in Soufriere Quarter called Malmaison, the proper noun of her now famous French residence. Information technology is likewise causeless that the de Taschers manor in Martinique was a pied-à-terre [occasional lodging] with his mother-in-law. St Lucia switched hands between England and French republic 14 times and at the fourth dimension of Josephine's birth there were no ceremonious registers on the island that would explain her baptism in Martinique; however, St. Lucia'south frequent change of ownership betwixt England and France could be seen equally the reason Josephine'south birthplace was left out on her birth record as it would have affected her nationality.

Descendants [edit]

Hortense's son, Napoleon III, became Emperor of the French. Eugène's son Maximilian de Beauharnais, third Duke of Leuchtenberg married into the Russian Majestic family, was granted the style of Imperial Highness and founded the Russian line of the Beauharnais family, while Eugene's girl Joséphine married Rex Oscar I of Sweden, the son of Napoleon's former fiancée, Désirée Clary. Through her, Joséphine is a direct ancestor of the present heads of the imperial houses of Belgium, Kingdom of denmark, Luxembourg, Kingdom of norway and Sweden and of the grandducal business firm of Baden.[ citation needed ]

A number of jewels worn by modern-mean solar day royals are often said to have been worn by Joséphine. Through the Leuchtenberg inheritance, the Norwegian royal family unit possesses an emerald and diamond parure said to have been Joséphine'southward.[ commendation needed ] The Swedish royal family owns several pieces of jewelry frequently linked to Joséphine, including the Leuchtenberg Sapphire Parure,[ citation needed ] a suite of amethyst jewels,[ citation needed ] and the Cameo Parure, worn by Sweden's royal brides.[ citation needed ] However, a number of these jewels were probably never a part of Joséphine'south collection at all, but instead belonged to other members of her family.[ citation needed ]

Another of Eugène'due south daughters, Amélie of Leuchtenberg, married Emperor Pedro I of Brazil in Rio de Janeiro, and became Empress of Brazil, and they had one surviving girl, Princess Maria Amélia of Brazil, who was briefly engaged to Archduke Maximilian of Austria before her early decease.[ citation needed ]

Nature and appearance [edit]

Biographer Carolly Erickson wrote, "In choosing her lovers [Joséphine] followed her head first, then her centre",[5] meaning that she was adept in terms of identifying the men who were most capable of fulfilling her financial and social needs. She was not unaware of Napoleon's potential. Joséphine was a renowned spendthrift and Barras may take encouraged the relationship with Général Bonaparte in lodge to get her off his easily. Joséphine was naturally full of kindness, generosity and amuse, and was praised as an engaging hostess.

Joséphine was described as beingness of average top, svelte, shapely, with silky, long, chestnut-brown hair, hazel eyes, and a rather sallow complexion. Her nose was pocket-sized and straight, and her rima oris was well-formed; however she kept it closed nearly of the time then as non to reveal her bad teeth.[25] She was praised for her elegance, way, and low, "silvery", beautifully modulated voice.[26]

Patroness of roses [edit]

In 1799 while Napoleon was in Arab republic of egypt, Josephine purchased the Chateau de Malmaison.[27] She had it landscaped in an "English" style, hiring landscapers and horticulturalists from the United Kingdom. These included Thomas Blaikie, a Scottish horticultural expert, another Scottish gardener, Alexander Howatson, the botanist, Ventenat, and the horticulturist, Andre Dupont. The rose garden was begun presently after purchase; inspired by Dupont's love of roses. Josephine took a personal interest in the gardens and the roses, and learned a smashing deal about botany and horticulture from her staff. Josephine wanted to collect all known roses so Napoleon ordered his warship commanders to search all seized vessels for plants to be forwarded to Malmaison.

Pierre-Joseph Redouté was commissioned by her to paint the flowers from her gardens. Les Roses was published 1817–xx with 168 plates of roses; 75–80 of the roses grew at Malmaison. The English nurseryman Kennedy was a major supplier, despite England and France beingness at war, his shipments were allowed to cross blockades. Specifically, when Hume's Chroma Tea-Scented Communist china was imported to England from China, the British and French Admiralties made arrangements in 1810 for specimens to cantankerous naval blockades for Josephine's garden.[28] Sir Joseph Banks, Director of the Purple Botanic Gardens, Kew, as well sent her roses.

The general assumption is that she had about 250 roses in her garden when she died in 1814. Unfortunately the roses were not catalogued during her tenure. At that place may have been only 197 rose varieties in existence in 1814, according to calculations by Jules Gravereaux of Roseraie de l'Haye. There were 12 species, about 40 centifolias, mosses and damasks, xx Bengals, and well-nigh 100 gallicas. The botanist Claude Antoine Thory, who wrote the descriptions for Redouté's paintings in Les Roses, noted that Josephine's Bengal rose R. indica had black spots on information technology.[29] She produced the first written history of the cultivation of roses, and is believed to have hosted the offset rose exhibition, in 1810.[thirty]

Modern hybridization of roses through artificial, controlled pollination began with Josephine'south horticulturalist Andre Dupont.[27] Prior to this, near new rose cultivars were spontaneous mutations or accidental, bee-induced hybrids, and appeared rarely. With controlled pollination, the appearance of new cultivars grew exponentially. Of the roughly 200 types of roses known to Josephine, Dupont had created 25 while in her employ. Subsequent French hybridizers created over 1000 new rose cultivars in the 30 years following Josephine'south death. In 1910, less than 100 years afterward her decease, at that place were nigh 8000 rose types in Gravereaux's garden. Bechtel besides feels that the popularity of roses as garden plants was boosted by Josephine'southward patronage. She was a pop ruler and fashionable people copied her.

Brenner and Scanniello call her the "Godmother of modern rosomaniacs" and attribute her with our mod style of vernacular cultivar names as opposed to Latinized, pseudo-scientific cultivar names. For instance, R. alba incarnata became "Cuisse de Nymphe Emue" in her garden. Subsequently Josephine'due south decease in 1814 the business firm was vacant at times, the garden and house ransacked and vandalised, and the garden's remains were destroyed in a battle in 1870. The rose 'Gift de la Malmaison' appeared in 1844, 30 years after her death, named in her honor by a Russian Thou Knuckles planting one of the commencement specimens in the Majestic Garden in St. Petersburg.[29]

Art patronage [edit]

Empress Josephine was a bully lover of all art. Her great interest in horticulture is well-known, but she too liked all things artistic. She surrounded herself with artistic people whose work ranged from paintings and sculpture to furniture and the compages all around her. Josephine always had an involvement in art merely information technology was with her union to her first husband that she would gain more access to art and artists. Due to her husband'due south high position in society she was oftentimes able to frequent many influential people's homes and learned from the works that were in their houses.[one] Afterwards marrying Napoleon and becoming Empress she was surrounded by the works of the time, however Josephine too appreciated the works of quondam masters. She was as well drawn to artists and styles that were non widely used in her fourth dimension, searching for artists that challenged the accustomed standards. She visited the Salon to build relationships with gimmicky artists. Josephine became a patron to several different artists, helping to build their careers though their connection to her. After buying the Château de Malmaison, Josephine had a bare canvas to showpiece her art and manner and used it to create salons, galleries, a theater and her infamous garden. The Malmaison and Tuileries Palace became centers for Napoleon'south government but was recognized every bit an important identify for the arts in whatsoever forms. Josephine'southward courtroom became the leading court in Europe for the arts. She became the starting time French female purple collector of this calibration, leading in the Consular and Empire Style.[31]

Antoine-Jean Gros,General Bonaparte at the Bridge of Arcole, 1796

Paintings [edit]

Josephine worked with and sought out the works of many artists throughout her lifetime. In the area of painters she mainly was a collector of paintings just she was painted by and worked with several artists such equally Jacques-Louis David and Francois Gerard. Notwithstanding, there was one painter whom Josephine favored and commissioned more oft than others, Antoine-Jean Gros. Gros, upon hearing that Josephine would exist visiting Genoa, worked to get an introduction knowing that the association with Josephine would help him become more well-known.

Upon meeting with Gros and seeing his work, Josephine asked him to come up back to Milan with her and to live in her residences. Josephine and so commissioned him to create a portrait of her hubby, the then General Napoleon. The work took several sittings between Gros and Napoleon and would be named "General Bonaparte at the Bridge of Arcole, November 17th,1796." This painting would become a large function of Napoleon's propaganda and iconography. Gros would go on to pigment other portraits of Napoleon, which always portrayed him as a fierce conqueror, propagating the image of Napoleon as powerful and unstoppable. Josephine every bit a supporter and patron of Gros, aided him in becoming a central conduit for the bulletin that the government was trying to disseminate almost the dominion of the Emperor in that time.

Sculpture [edit]

Antonio Canova Dancer with Her Hands on her Hips, 1812

Over her lifetime Josephine commissioned iv major pieces from the Italian Neoclassical sculptor Antonio Canova. The Empress was given a re-create of Canova's work Psyche and Cupid, which was originally promised to Colonel John Campbell, but because of unforeseen circumstances it was gifted to Josephine. She would commission Canova to create a sculpture and the result would be Dancer with Hands on Hips. The work deputed in 1802 simply was not finished until 1812, Josephine allowed him to create on his own terms, which were based on the classics simply with a more relaxed and blithesome appearance. He would create several sculptures based on dancing. Dancer with Easily on Hips was praised by the fine art community because it was not based on whatsoever specific ancient sculpture, but with a classical spin, making information technology a completely original sculpture.

Josephine would commission Canova again for some other sculpture called Paris. The piece of work'due south plaster cast was completed in 1807 but the marble statue was non finished until 1812. arriving in Malmaison in 1813 a year before Josephine'south death. The last sculpture that the Empress would commission was The Iii Graces. This work would not be completed until later Josephine'southward decease in 1816. All four works were eventually sold to Tsar Alexander of Russian federation.[32]

Furniture/Design [edit]

The architects Charles Percier and Pierre Fontaine substantially became the decorators for Josephine and Napoleon. Many of Josephine's most well-known furnishings were created especially for her by Percier and/or Fontaine. The ii architects worked within many of the Empire's residences, creating spaces for the Empress to feel at dwelling in. Percier and Fontaine had their ain unique mode and created pieces for both the Emperor and his Empress, which tin be hands identified as their work, even when they were not stamped as created by Percier or Fontaine. Percier and Fontaine are known for their apply of cheval drinking glass and the utilize of a feminine, softer feel for the pieces used in the boudoir of the Empress. These pieces were unique for the time and appreciated for their inventiveness. The architects Percier and Fontaine are continued to the Empire style associated with the time period.[33]

Arms [edit]

In pop civilisation [edit]

Statue [edit]

In 1859, French emperor Napoleon Three commissioned a statue of Josephine, which was installed in the La Savane Park in downtown Fort-de-France. In 1991, the statue was symbolically decapitated and spattered with red paint. The acts of vandalism were washed on the belief that Joséphine had influenced her husband to effect the Constabulary of xx May 1802, which reinstated slavery in the French colonial empire (including Martinique).[34] The statue was never repaired past the city administration, and every yr more reddish paint was added to it.[35] In July 2020, the statue was torn down and destroyed by anti-racism protestors in the wake of the George Floyd protests.[36]

Fiction books [edit]

- Conan Doyle, Sir Arthur (1897). Uncle Bernac.

- Fields, Bertram (2015). Destiny: A Novel Of Napoleon & Josephine.

- Gulland, Sandra (1995). The Many Lives & Secret Sorrows of Josephine B.

- ——— (1998). Tales of Passion, Tales of Woe.

- ——— (2000). The Final Great Dance on Earth.

- Kenyon, F. W. (1952). The Emperor's Lady.

- Mossiker, Frances (1965). Napoleon and Josephine.

- ——— (1971). More Than a Queen: The Story of Josephine Bonaparte.

- Pataki, Allison (2020). The Queen's Fortune: Desiree, Napoleon, and the Dynasty That Outlasted the Empire.

- Selinko, Annemarie (1958). Désirée.

- Webb, Heather (2013). Becoming Josephine.

- Winterson, Jeanette (1987). The Passion.

Television [edit]

- Napoléon and Josephine: A Beloved Story (1987) is a miniseries with Napoleon portrayed past Armand Assante and Josephine by Jacqueline Bisset.

- Napoléon (2002) is a historical DVD Television miniseries of Napoleon'southward life, in which Josephine features prominently, portrayed by Isabella Rossellini.

- In 2015 and 2017, an episode of Horrible Histories called "Naughty Napoleon" and "Ridiculous Romantics" featured Natalie Walter and Gemma Whelan, portraying Joséphine de Beauharnais.

Picture [edit]

- Ridley Scott 's upcoming 2023 moving picture Kitbag in which Vanessa Kirby will play Joséphine. Jodie Comer was originally cast only had to driblet out practice to scheduling conflicts and the COVID-19 pandemic.[37]

Music [edit]

- The beloved song 'Josephine' from The Magnetic Fields' 1991 album Distant Plastic Trees: "If I were Napoleon, you could be my Josephine ..."

- The song 'Josephine' from Frank Turner's 2015 album Positive Songs for Negative People references Josephine — too as Josephine Brunsvik — to portray Turner's wish that he has his own muse to influence him.

- The song 'Josephine' from Tori Amos' 1999 partially alive album To Venus and Back references the popular-civilisation expression, supposedly spoken by Napoleon: "Not this evening, Josephine".

Manner [edit]

- Galliano said that his inspiration was dressing the pregnant stone star Madonna — and then thinking "Empress Josephine."[38]

Encounter also [edit]

- Aimée du Buc de Rivéry

- Notre Dame de Paris

- The Swedish Imperial Family's jewelry

- Tuileries Palace

References [edit]

- ^ a b Delorme, Eleanor P. Josephine and the Arts of the Empire. Los Angeles: The J. PaulGetty museum, 2005, ane.

- ^ Branda, Pierre (2016). Josephine: Le Paradoxe du Cygne. Paris: Perrin. p. 9.

- ^ "Sights in Trois-Îlets". Lonely Planet.

- ^ a b c d Andrea Stuart: Josephine: The Rose of Martinique.

- ^ a b Erickson, Carolly (2000). Josephine: A Life of the Empress. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. p. 82. ISBN0-312-26346-5.

- ^ Stuart, Andrea (2005). The Rose of Martinique: A Life of Napoleon's Josephine. Grove Press. p. 489. ISBN978-0802117700.

- ^ Wiliams, K. (2014). Ambition and Desire: The Dangerous Life of Josephine Bonaparte. New York: Random House.

- ^ Epton, Nina (1975). Josephine, the Empress and Her Children. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., pp. 54, 66–67.

- ^ Hippolyte Charles Archived 27 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Theo Aronson, Napoleon and Josephine: A Love Story.

- ^ "Madame Pauline Fourès-Napoleon'due south Cleopatra". Archived from the original on thirty May 2012. Retrieved xv March 2012.

- ^ "抖音歌曲_抖音排行歌曲_抖音英文音乐_抖音闽南音乐【573音乐网】". world wide web.emmetlabs.com.

- ^ Epton, p. 94.

- ^ Epton, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Epton, p. 95.

- ^ Tschudi, Clara (1900). The great Napoleon's female parent. Cornell University Library. New York, E. P. Dutton.

- ^ E. Bruce, Napoleon and Josphine, London : Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1995, pg.445.

- ^ "Napoleon: Napoleon and Josephine". PBS . Retrieved 29 Dec 2018.

- ^ Esdaile, Charles (27 October 2009). Napoleon's Wars: An International History. Penguin. ISBN9781101464373.

- ^ Arnold, James R. (1995). Napoleon Conquers Republic of austria: The 1809 Campaign for Vienna. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 194. ISBN9780275946944.

- ^ Recueil général des lois et des arrêts, book 38, Bureaux de l'Administration du recueil, 1859, p. 76.

- ^ "Empress Josephine's brusk biography in Napoleon & Empire website, displaying photographs of the castle of Malmaison and the grave of Josephine". Napoleon-empire.com. xi June 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ^ Markham, Felix, Napoleon, p. 245.

- ^ "Notes and Queries, Vol. Five, Number 123, March 6, 1852 | A Medium of Inter-communication for Literary Men, Artists, Antiquaries, Genealogists, etc. | Page 220". Project Gutenberg . Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ Epton, Nina (1975). Josephine, The Empress and Her Children. New York: W. W. Norton & Visitor, Inc. p. 3.

- ^ Mossiker, Frances, Napoleon and Josephine, p. 48.

- ^ a b Bechtel, Edwin de Turk. 1949, reprinted 2010. "Our Rose Varieties and their Malmaison Heritage". The OGR and Shrub Journal, The American Rose Society. 7(3)

- ^ Thomas, Graham Stuart (2004). The Graham Stuart Thomas Rose Volume. London, England: Frances Lincoln Limited. ISBN 0-7112-2397-1.

- ^ a b Brenner, Douglas, and Scanniello, Stephen (2009). A Rose by Any Name. Chapel Hill, N Carolina: Algonquin Books.

- ^ Bowermaster, Russ (1993). "Judging: From Whence to Hence". The American Rose Annual: 72–73.

- ^ Delorme, Eleanor P. Josephine and the Arts of the Empire. Los Angeles: The J. PaulGetty museum, 2005, 3–4.

- ^ "Empress Josephine's Collection of Sculpture by Canova at Malmaison." Journal of the History of Collections sixteen, no. one (May 2004): 19–33.

- ^ Samoyault, Jean-Pierre. "Article of furniture and Objects Designed by Percier for the Palace of Saint-Deject." The Burlington Mag 117, no. 868 (1975): 457–65.

- ^ Bennett, Steve (4 October 2012). "Uncommon Caribbean - Beheaded Statue of Empress Josephine: Uncommon Attraction". Uncommon Caribbean.

- ^ "The Headless Empress". www.atlasobscura.com/.

- ^ "Anti-Racism Activists Destroy Statue Of Napoleon'southward Kickoff Wife Josephine In Martinique". NDTV. NDTV. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ "'Killing Eve' Star Jodie Comer Confirmed for Ridley Scott's 'Kitbag' Opposite Joaquin Phoenix". Variety. 3 September 2021.

- ^ Menkes, Suzy (viii July 1996). "Galliano's Empire Line Shines for Givenchy". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- Aronson, Theo (1990). Napoleon and Josephine: A Love Story. St Martins Pr. ISBN0-312-05135-2.

- Brent, Harrison. (1946). Pauline Bonaparte, A Woman of Affairs. NY and Toronto Rinehart.

- Bruce, Evangeline. (1995). Napoleon and Josephine: An Improbable Marriage. NY: Scribner. ISBN 0-02-517810-5

- Castelot, André (2009). Josephine. Ishi Printing. ISBN978-iv-87187-853-one.

- Chevallier, Bernard; Pincemaille, Christophe. Douce et incomparable Joséphine. éd. Payot & Rivages, coll. «Petite bibliothèque Payot», Paris, 2001. ISBN 2-228-90029-X

- Chevallier, Bernard; Pincemaille, Christophe. L'impératrice Joséphine. Presses de la Renaissance, Paris, 1988., 466 p.,ISBN 978-2-85616-485-three

- Delorme, Eleanor P. (2002). Josephine: Napoleon's Unequalled Empress. Harry North. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-1229-8

- Epton, Nina. (1975). Josephine: the Empress and Her Children. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-393-07500-seven

- Erickson, Carolly (1998). Josephine; A Life of the Empress. St. Martin's Press. ISBN1-86105-637-0.

- Fauveau, Jean-Claude. Joséphine l'impératrice créole. L'esclavage aux Antilles et la traite pendant la Révolution française. Éditions L'Harmattan 2010. 390 p. ISBN 978-2-296-11293-iii.

- Knapton, Ernest John. (1963). Empress Josephine Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-671-51346-7

- de Montjouven, Philippe. Joséphine: Une impératrice de légendes. Timée-éditions; 2010, 141 p. ISBN 978-two-35401-233-5

- Mossiker, Frances (1964). Napoleon and Josephine; the Biography of a Matrimony. Simon and Schuster. ISBN978-0-00-000000-2.

- Schiffer, Liesel. Femmes remarquables au Nineteen siècle. Vuibert éd. Vuibert, Paris, 2008, 305 p. ISBN 978-2711744428

- Sergeant, Philip (1909). The Empress Josephine, Napoleon's Enchantress. NY: Hutchinson'due south Library of Standard Lives.

- Stuart, Andrea. (2005). The Rose of Martinique: A Life of Napoleon'southward Josephine. Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-4202-3

- Wagener, Françoise, L'Impératrice Joséphine (1763–1814). Flammarion; Paris, 1999, 504 p.

External links [edit]

-

The Heroines of History public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Heroines of History public domain audiobook at LibriVox - Empress Josephine past Ernest John Knapton. Complete transcription of the 1963 biography.

- Joséphine de Beauharnais (de Tascher de la Pagerie) (in French). Site published by the current members of the family Tascher de la Pagerie.

- Château de Malmaison (in French), Joséphine'southward residence from 1799 to 1814, the site of her death.

- Memoirs of the Empress Josephine (Volume ane) at archive.org

- Memoirs of the Empress Josephine (Volume 2) at archive.org

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Empress_Jos%C3%A9phine

0 Response to "Napoleon Art and Court Life in the Imperial Palace Catalog Pdf"

Postar um comentário